Edward James Eliot: Happiness and Heartbreak

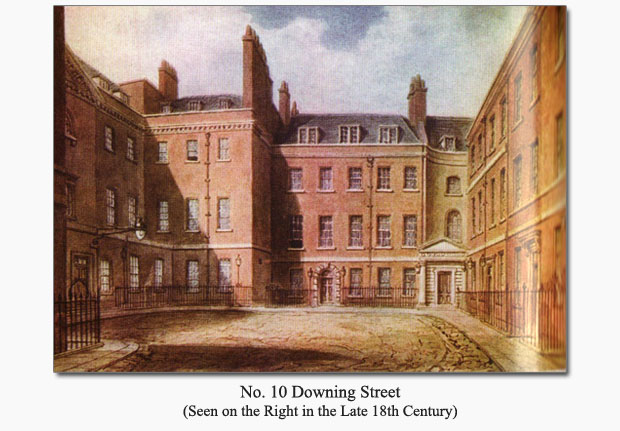

As a happy pair, Edward James and Harriot continued on at Putney for a time after their marriage, with as many moments spent in the country as possible (when the political scene allowed). Business eventually called them back to London, however, and they proceeded to Downing Street to stay with her brother for a time. Harriot was a remarkable young woman and genuinely loved and admired by all who met her. She was, observed a family friend, "a very beautiful woman", possessed of every quality "which could make her amiable and attractive". Together, she and Edward James must have made quite an impression, and all facets of London society were certainly open to them. Life went on as blissfully as the happy pair could imagine, and so much time was spent near the Dowager Lady Chatham (Harriot's mother) that few letters survive to shed light on what Edward James would forever remember as the best year of his life. Harriot was soon expecting their first child, and the couple looked forward to their new life as a family of three. Edward James found time to purchase a new "very fine dashing grey horse" of very "inquiet" disposition. This gave more than a little worry to his poor wife, who was proved correct in her concerns when she saw the horse returning home to Downing Street one day without a rider. She immediately ran up to her husband's room, discovering him there, already returned, and nursing a very lame knee. "Thank God there is no material hurt," she wrote to her mother the following day, "as he did not get any blow upon the head." Harriot put her wifely foot down, also informing her mother that "the horse is to be sold directly". So continued their happy life together.

As time passed, Harriot's letters to her mother continued, documenting political news and a few of the mundane events of the couple's home life. By April, Edward James and Harriot were settled in London, where she observed "by the London glasses" that they certainly looked much better for the country air. Edward James was voted by his wife to be "in supreme beauty", having not looked so perfectly well since his accident a few months before. Harriot herself was having a difficult pregnancy, experiencing abnormal pains and symptoms, though she remained very optimistic in her regular reports to her worried mother. Harriot's only sister had passed away a few months after giving birth to her third child, so Lady Chatham was obviously very worried about Harriot's problems.

Edward James and Harriot spent the summer in London, still staying at Downing Street with Pitt, and it was there, on the twentieth of September 1786, that they welcomed a baby girl. The new parents and uncle were overjoyed, immediately sending out letters announcing the good news. Pitt took quill in hand to tell his mother of the birth of this new granddaughter:

"I have infinite joy in being able to tell you that my sister has just made us a present of a girl, and that both she and our new guest are in every way as well as possible. . . . She was in perfectly good spirits thro' the whole of the time and suffered no more than was natural."

This was an hour of supreme happiness and exultation for the new parents, but its joys soon faded into worries. Within two days, Harriot had a bad night and a "little fever." No immediate danger was thought of, and Harriot appeared to feel better — but the alarming symptoms soon returned. By the twenty-fourth, Harriot's condition had degenerated so rapidly that all hope was given up for her recovery. Edward James and Pitt stayed in the house at Downing Street for thirty hours straight, one or the other of them never leaving her side, as a full realization of the eventual outcome of the situation hung like a black cloud over the family. At eleven o'clock on Sunday morning, anticipating the imminent demise of his beloved sister, Pitt wrote a letter of warning to Lady Chatham's friend and companion, Mrs. Stapleton, asking her to break the sad news to his mother in whatever manner she thought best. Harriot continued calm and collected. When she felt her strength fading, she asked that Rev. Dr. Pretyman be sent for, in order that he might comfort her through the administration of the Sacrament. This done, she "affectionately took leave of her dear and tender connections, and sank into the arms of her Saviour and Creator." Harriot passed away on Sunday afternoon – October 25, 1786 – just one day after her first wedding anniversary and five days after giving birth to their first and only child.

Edward James was completely crushed by the death of his wife, and it may even be fitting to say that part of him died that day with her. According to Wilberforce (who knew him as well as a brother), his "natural temper" was "ill calculated for bearing up against such a stroke". While Pitt had pressing matters of government business that helped to distract him from his grief, nothing could distract Edward James from his overwhelming sorrow. Pitt refused to leave him alone. John Eliot was in Cornwall at the time of his sister-in-law's death, but he set out for London immediately on hearing the news. Until John's arrival, Pitt refused even to travel to Burton to attend his mother, explaining: "I should not lose a moment, you will believe, in coming to Burton, but I am sure you will approve of my not leaving poor Eliot at this time, for whom we have all, and I most especially, so many affecting reasons to interest us. His mind begins to be as composed as could yet be expected."

Harriot's funeral took place on the second day of October, eight days after her death. She was placed near her father in the Chatham vault in the North Transept of Westminster Abbey. From the beginning, Edward James insisted on "paying every respect and attention which imagination" could suggest to her memory, saying that it was "much of the little consolation" he had left. This played out very expensively in Harriot's funeral, with the distraught husband paying more than £200 to a Mr. Henry Turner for an intricate aristocratic funeral — full details of which survive and serve as an ample illustration of why so many British aristocrats (most Eliots among them) left explicate instructions in their wills insisting on inexpensive and simple funerals. (Rather inexplicably, this impressive funeral does not appear to have been reported in any of the daily papers — a particularly odd fact, considering the grandeur of it and the deceased's connection to the Earl of Chatham.)